The uncertain photograph is confused as to what present to record. (…)

The uncertain photograph transforms objects into photographic objects.

The uncertain photograph uses time as a medium. (…)

The uncertain photograph cannot be reduced to mere information or representation.

-Brice Bischoff

If one types “long exposure photography” into the appropriate search engine the results will show millions of landscapes and cityscapes: spectacular images of beautiful bridges, pastoral waterfalls and busy streets. There will be carousels with aureoles of strange psychedelic light as well as sublime cliffs bathed in the same artificial glow. Most of the photographs combine smooth, almost ghostlike objects with sharply rendered structures. However, notably missing from these rather spectacular images is the intimacy of an indoor-setting. Judging from the results of this search it would seem that the technique of long exposure photography lends itself primarily to the clashing binaries of sublime landscapes and man-made structures, darkness and light, movement and stillness. Although varied in their settings, most, if not all of the images refer to the basic photographic conditions of light and time while speaking to the photographers’ paradoxical desire to render passing time visible; to pause, hold and record it. At the dawn of photography in the early 19th century people had to stand still and hold a pose for up to ten minutes in order to achieve the desired effect: the indexical imprint on a plate (and later, film) which was then considered authentic, almost a double of the original. In these early portraits, every undisciplined bodily movement–a subtle gesture, the wink of an eye, or a transient smile–had to be repressed in order to render the subject as sharply as possible. The movements of an unruly child squirming on her mother’s lap would have been unintentionally documented, resulting in the child’s face appearing distorted and blurry. While these distortions were once considered the manifestation of a double failure–the child lacking self–control as well as the mother and photographer being incapable of disciplining her–this form of movement in time has now become highly desired. The contemporary practice of long exposure photography presents time as condensed, composed of layers that are sometimes more translucent than opaque, with action and movement creating shadows or milky, foggy surfaces. Does this technique signal a return of the repressed? Does it mark the desire to perceive not only human bodies but the world and its objects as animated?

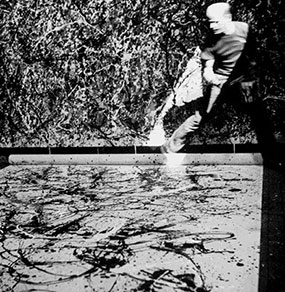

Brice Bischoff’s Glassell Park Series plays precisely off of this paradoxical moment. Unlike photography’s obsession with rendering movement visible–as in Muybridge’s and Marey’s serial photographic studies of motion–Bischoff’s “uncertain photographs” obscure the process again, working against our desire to perceive and recognize. In his Glassell Park Series the long debate about the photographic sign existing as a transparent “window” into the world in contrast to being self–referential and opaque becomes irrelevant, the binary is fused or rather confused (like the photographic objects themselves). Bischoff’s series also refers to the place of its production, the artist’s studio in Glassell Park in North–East Los Angeles, which is rendered as the site of production par excellence. Modernism, and post–War Modernism in particular, seems to have been obsessed with the image of the artist in his studio. Photographers–most famously Hans Namuth’s photos of a paint–spattered and focused Jackson Pollock–helped in creating and circulating the myth–making images of the virile, active, manic artist or the pensive, quiet, slightly depressed one. The modern myth of the studio as a symbol for artistic genius and creativity came to life already in the 19th century and from then on was constantly “re–invented” as allegories referring to various aspects of the artist’s work.1

But Bischoff’s images do not perpetuate this myth. As so often in his practice he refers to historically canonized conventions while simultaneously breaking them: the photos do not show him taking a photo of himself in the studio (although this is also what we see) but several objects captured in various stages of opacity in a setting that is reminiscent of a studio while the interior architecture functions as a mere backdrop. In times of post-studio practices, art and/as research, ephemeral performances and site–specific installations, Bischoff shows us the studio as a place of almost mystic transformations and emanations: an aspect of the studio that seems to have been abandoned by the “dematerializing” tendencies of conceptual art. Concluding, however, that these staged scenes celebrate an anachronistic idea of artistic inspiration and creative genius would be to ignore their often satirical character. They include objects that have potentially been produced in some studio, and on a closer look, often consist of seemingly random elements; some sculptures are made out of everyday objects, even rubbish; some of them were produced by Bischoff’s friends, such as the mural painted by Swiss artist Charlotte Herzig and the drywall benches donated by Seth Weiner after being used in a sound installation. Though these objects refer to the different genres and types of art produced in a studio, they also playfully evoke clichés of art making and its power dynamics. In one of the compositions the female model/muse is rendered almost comically passive: She is lying on a bench, presenting her naked back to the gaze of both the active male artist and the audience. But again these conventions are undermined because the female body coalesces so much with its surroundings of drywall, fabric and light that everything appears to be of a different molecular structure; becoming–woman or becoming–image? Gilles Deleuze has called the pure vision of the non–human eye “gaseous perception” which refers to a different mode of thinking about movement and action, achieved here by the photographic technique of bending time and visibility.

Brice Bischoff’s Glassell Park Series plays precisely off of this paradoxical moment. Unlike photography’s obsession with rendering movement visible–as in Muybridge’s and Marey’s serial photographic studies of motion–Bischoff’s “uncertain photographs” obscure the process again, working against our desire to perceive and recognize. In his Glassell Park Series the long debate about the photographic sign existing as a transparent “window” into the world in contrast to being self–referential and opaque becomes irrelevant, the binary is fused or rather confused (like the photographic objects themselves). Bischoff’s series also refers to the place of its production, the artist’s studio in Glassell Park in North–East Los Angeles, which is rendered as the site of production par excellence. Modernism, and post–War Modernism in particular, seems to have been obsessed with the image of the artist in his studio. Photographers–most famously Hans Namuth’s photos of a paint–spattered and focused Jackson Pollock–helped in creating and circulating the myth–making images of the virile, active, manic artist or the pensive, quiet, slightly depressed one. The modern myth of the studio as a symbol for artistic genius and creativity came to life already in the 19th century and from then on was constantly “re–invented” as allegories referring to various aspects of the artist’s work.1

But Bischoff’s images do not perpetuate this myth. As so often in his practice he refers to historically canonized conventions while simultaneously breaking them: the photos do not show him taking a photo of himself in the studio (although this is also what we see) but several objects captured in various stages of opacity in a setting that is reminiscent of a studio while the interior architecture functions as a mere backdrop. In times of post-studio practices, art and/as research, ephemeral performances and site–specific installations, Bischoff shows us the studio as a place of almost mystic transformations and emanations: an aspect of the studio that seems to have been abandoned by the “dematerializing” tendencies of conceptual art. Concluding, however, that these staged scenes celebrate an anachronistic idea of artistic inspiration and creative genius would be to ignore their often satirical character. They include objects that have potentially been produced in some studio, and on a closer look, often consist of seemingly random elements; some sculptures are made out of everyday objects, even rubbish; some of them were produced by Bischoff’s friends, such as the mural painted by Swiss artist Charlotte Herzig and the drywall benches donated by Seth Weiner after being used in a sound installation. Though these objects refer to the different genres and types of art produced in a studio, they also playfully evoke clichés of art making and its power dynamics. In one of the compositions the female model/muse is rendered almost comically passive: She is lying on a bench, presenting her naked back to the gaze of both the active male artist and the audience. But again these conventions are undermined because the female body coalesces so much with its surroundings of drywall, fabric and light that everything appears to be of a different molecular structure; becoming–woman or becoming–image? Gilles Deleuze has called the pure vision of the non–human eye “gaseous perception” which refers to a different mode of thinking about movement and action, achieved here by the photographic technique of bending time and visibility.

Bischoff’s practice also reflects the long shared history of performance and photography, be it the pre–cinematographic magic lantern and camera obscura shows that were “performed” live, photography’s role in 1960s and 70s performance art or the highly choreographed photographic settings of the 1990s. Bischoff’s actions, though, are staged specifically for the camera and not for an audience; a strategy which reflects photography’s double nature of functioning as document as well as simulation. With its treatment of objects as “actors”, The Glassell Park Series follows a similar trajectory as the German artist–couple Anna and Bernhard Blume who started collaborating on photographic works in the late 1970s. “We have aimed at creating an ironic activism critical of fear, which is staged work by work, composing images according to the rules of abstract painting,”2 the Blumes stated in 2002, and referred to their practice as “transcendental constructivism“–a term that loosely applies to Bischoff’s work. Although these two (or three) artists share anti–realist photographic tendencies, their practices overlap most in relation to their treatment of the world of objects. To quote the Blumes again, “…things and objects, long subjected to human will, somehow come to life in our photographs, and, in turn, in a spiritualistic leap, they ‘objectify’ the human protagonists.”3 Though Bischoff would probably argue against this spiritualistic side in favor of a more rational explanation of objects seen within the layers of time, his object–performances can be productively read within the recent debate of an anti–subject–centered philosophy that concentrates on an animated “world of things.” Philosopher Bruno Latour, in his book “We Have Never Been Modern”4 pleads for the acknowledgement of an object’s capacity to act. He argues that because within every encounter a reciprocal transfer between subject and object occurs, we cannot consider objects as passive anymore. Far from an approach of looking for the essence of things, Latour sees these objects refusing distinct interpretation.

In The Glassell Park Series, the objects which are transformed by Bischoff’s “uncertain photographs” appear as markers, even translators for a larger debate about studio practices and the site of (artistic) production: By rendering the studio as a place no different than any other, the images work to overcome the mythologizing of an artist’s studio while simultaneously testifying to a post–conceptual desire for materiality..5 Within this matrix of discourses Mr. Bischoff presents his studio as a place of shifting practices and of temporal collaborations: autonomous but not solitary.

1 See Barry Schwabsky essay, “The Symbolic Studio,” for a little history on the topic. In: the studio reader, ed. by Mary Jane Jacob and Michelle Grabner, Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press 2010, 88-96

2 Anna and Bernhard Blume, “From A to Z,” in: exit #7: Teamwork, August/October 2002, Madrid. http://www.exitmedia.net/eng/num7/blume.html, retrieved on Feb 7th, 2013.

3 Ibid.

4 Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, (transl. from French) Cambridge/Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993.

5 A tendency that can even be traced to the current renaissance of crafting, gardening, farming as diy practices in a broader sense.

Bischoff’s practice also reflects the long shared history of performance and photography, be it the pre–cinematographic magic lantern and camera obscura shows that were “performed” live, photography’s role in 1960s and 70s performance art or the highly choreographed photographic settings of the 1990s. Bischoff’s actions, though, are staged specifically for the camera and not for an audience; a strategy which reflects photography’s double nature of functioning as document as well as simulation. With its treatment of objects as “actors”, The Glassell Park Series follows a similar trajectory as the German artist–couple Anna and Bernhard Blume who started collaborating on photographic works in the late 1970s. “We have aimed at creating an ironic activism critical of fear, which is staged work by work, composing images according to the rules of abstract painting,”2 the Blumes stated in 2002, and referred to their practice as “transcendental constructivism“–a term that loosely applies to Bischoff’s work. Although these two (or three) artists share anti–realist photographic tendencies, their practices overlap most in relation to their treatment of the world of objects. To quote the Blumes again, “…things and objects, long subjected to human will, somehow come to life in our photographs, and, in turn, in a spiritualistic leap, they ‘objectify’ the human protagonists.”3 Though Bischoff would probably argue against this spiritualistic side in favor of a more rational explanation of objects seen within the layers of time, his object–performances can be productively read within the recent debate of an anti–subject–centered philosophy that concentrates on an animated “world of things.” Philosopher Bruno Latour, in his book “We Have Never Been Modern”4 pleads for the acknowledgement of an object’s capacity to act. He argues that because within every encounter a reciprocal transfer between subject and object occurs, we cannot consider objects as passive anymore. Far from an approach of looking for the essence of things, Latour sees these objects refusing distinct interpretation.

In The Glassell Park Series, the objects which are transformed by Bischoff’s “uncertain photographs” appear as markers, even translators for a larger debate about studio practices and the site of (artistic) production: By rendering the studio as a place no different than any other, the images work to overcome the mythologizing of an artist’s studio while simultaneously testifying to a post–conceptual desire for materiality..5 Within this matrix of discourses Mr. Bischoff presents his studio as a place of shifting practices and of temporal collaborations: autonomous but not solitary.

1 See Barry Schwabsky essay, “The Symbolic Studio,” for a little history on the topic. In: the studio reader, ed. by Mary Jane Jacob and Michelle Grabner, Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press 2010, 88-96

2 Anna and Bernhard Blume, “From A to Z,” in: exit #7: Teamwork, August/October 2002, Madrid. http://www.exitmedia.net/eng/num7/blume.html, retrieved on Feb 7th, 2013.

3 Ibid.

4 Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, (transl. from French) Cambridge/Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993.

5 A tendency that can even be traced to the current renaissance of crafting, gardening, farming as diy practices in a broader sense.